The Bedouins: Squatters on their own land

Catherine Weibel

Catherine Weibel reports on the Bedouin tribes of the Negev desert, a people whose semi-nomadic traditions have placed them in legal no-man’s land with the Israeli government.

published on Oxfam International

_________________________________________________________________

A precarious situation

The remains of demolished houses can be found in many unrecognized villages in the Negev desert. Credit: Catherine Weibel/Oxfam

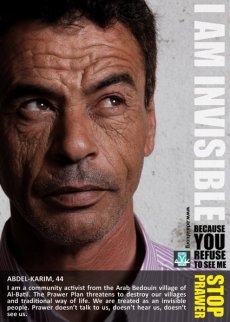

In Jerusalem, most souvenir shops sell postcards depicting camels crossing the Negev desert, which covers most of southern Israel. These cards rarely feature the people who’ve been roaming the desert for centuries alongside these camels, the Arab Bedouin. Many still live in a precarious situation, some 60 years after they were displaced from their lands during the early days of the State of Israel.

Today, the Negev (or “Naqab” in Arabic, as the Bedouin call it) is home to an estimated 160,000 Bedouin, about half of whom are living in villages considered illegal by the Israeli authorities, who have continually pressured the Arab Bedouin to give up their traditional, semi-nomadic ways for a more sedentary life.

As Israeli General Moshe Dayan put it in 1963, the goal was to turn the traditional Bedouin into someone “who would not live on his land with his herds, but would become an urban person who comes home in the afternoon and puts his slippers on.”

Morad El-Sana, a lawyer who worked for eight years with the Oxfam-supported partner organization Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, explains that historically, the Arab Bedouin are neither rootless nor landless people. “Each tribe used to have its own specific area in the Negev,” he says. “They led a semi-nomadic life, herding cattle and cultivating the land, with one village for the summertime and another during the winter to ensure their herds had enough grazing lands.”

Unrecognized villages

Today, about half of the Negev Bedouin have left their lands and moved to one of the seven legal, government-built villages. The other half remained on their land in 45 villages that are not recognized by the Israeli authorities and which, as if invisible, do not appear on commercial maps. These unrecognized villages receive little to no services. They lack basic transportation infrastructure, including roads. They have no access to power or water networks and offer few educational or health facilities, even though the Bedouin are Israeli citizens.

Many unrecognized villages are scattered a few minutes drive from modern highways but they still present a scene of appalling poverty, with bare-foot children running amid corrugated iron and wooden huts. The remains of demolished houses can be found in most of the village – the authorities tore the huts down as their inhabitants have not been granted construction permits, even though they have sometimes been living on a particular plot of land for decades.

El-Sana explains that the Negev is said to be “dead land” by Israeli authorities. They rely on an ancient Ottoman law from the 1820s to back up that legal claim. In practice, it means that the Bedouin of 2010 cannot claim ownership of the ancestral lands their families and tribes have been using for centuries.

An inadequate alternative

The seven government-planned towns, which were built without consulting the Bedouin communities, have proven an inadequate alternative due to decaying infrastructure, a lack of consideration for Bedouin family ties and a high unemployment rate. Although the Arab Bedouin do get some benefits from the state, such as healthcare and child allowances, it is not enough to help them escape from poverty. Travel distances to schools are so long, for example, that 77% of Bedouin girls end up dropping out of school, according to El-Sana.

The towns are also ill-equipped to handle any influx of new residents and lack the space to accommodate traditional livelihoods such as herding. Some of them look little better than shanty towns. They are a far cry from the shiny, modern cities which have been built recently to house other Israeli communities in the Negev.

“I want to stay on my land”

“I want to stay on my land, which has been passed from one generation to another in my family,” a Bedouin resident of one of the unrecognized villages told Oxfam. “If I leave and I move to one of the legal cities, I will lose any claim on my land and so will my children. I want the state to let us live legally in our house, on our land.”

Oxfam’s partner Adalah brings impact litigation cases before the Israeli courts to promote and defend the rights of the Arab Bedouin in the country, primarily in the fields of land and housing rights, health and education rights. Adalah advocates for an official recognition of the “unrecognized villages” by the Israeli authorities so that the Arab Bedouin living in these villages can stay on their lands and their ongoing forced displacement comes to an end.

כתיבת תגובה